Persian Language and Iranian/Persianate Studies Faculty

Persian Studies Lecture Series

Persian Language at UChicago (Farsi / Dari / Tajiki = тоҷикӣ /فارسی / دری)

Persian = Farsi? Dari? Tajiki?

Persian in the Workplace

Persian Study at UChicago

Persian Student Essay Prize

Persian Language, Culture, and Literature Courses Offered at the University of Chicago

Persian Language Courses

Iranian/Persianate Studies Courses

Major and Minor

Persian Placement Test

Persian Circles

Literature in Persian Language Pedagogy Webinar

AI-Driven Language Pedagogy for Less Commonly Taught Languages Webinar

Persian Language and Iranian/Persianate Studies Faculty

Persian Faculty in Other Departments

Alireza Doostdar (Divinity School)

Yousef Casewit (Divinity School)

Gregory Maxwell Bruce (South Asian Languages & Civilizations)

2025-2026 Persian Studies Lecture Series

April, 8 2026- Heshmat Moayyad memorial lecture – Prof. Arezou Azad, Senior Research Fellow at the Department of Continuing Education at the University of Oxford and Junior Professor and Chair of the Arts and Heritage of Afghanistan at the Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales (Inalco) in Paris. Title TBA.

Persian Language at UChicago (Farsi / Dari / Tajiki = тоҷикӣ /فارسی / دری)

Persian is the official language of today’s Iran, and one of the two official languages in both Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Outside of Afghanistan, Iran and Tajikistan, Persian is still spoken by a significant minority in Uzbekistan, and by diaspora communities throughout North America, Europe, Israel and Australia. All in all, an estimated 110 million people throughout the globe speak Persian, placing it among the top 20 or so world languages in terms of the number of speakers.

Historically Persian served as a prestige language of literature and administration across a large swath of Central Asia; in southwest Xinjiang province, China; in South Asia (including Kashmir, Pakistan, northern India, Bengal, and the Deccan); in the Caucasus (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Daghestan); in the Ottoman territories of Anatolia and the Balkans; in parts of Iraq (especially near the Shi`i shrines in Najaf and Karbala); and along the Persian Gulf littoral, as well as on the Iranian plateau. It was also a widespread spoken koine throughout much of Asia along the Silk Route. Scholars today refer to this area where the Persian language and/or its literary, political and administrative culture held sway as the “Persianate” zone.

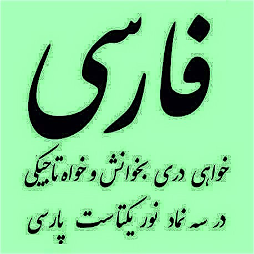

Persian = Farsi? Dari? Tajiki?

The Greeks gave us the name Persia (Περσῐ́ς) after Old Persian Pārsa, the name for the province in south central Iran at the center of the Achaemenid empire, and it remained the name of the country until 1935 when Reza Shah officially pronounced the modern nation-state would henceforth be called Iran.

Although Persian is mutually understood by educated speakers from eastern Iraq through to the borders of China, Persian speakers in Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan use different names when describing their common language. In Iran, Persian speakers call the language Fârsi, or Pârsi (فارسی / پارسی); in Afghanistan, the 1962 constitution officially recognizes the language as Dari ((دری; and in Tajikistan– where the language has been written in the Cyrillic script since WWII – it is officially known as Tâjiki, or Tojiki (тоҷикӣ). In the modern era of nation-states with different ideologies, distinct educational and administrative systems, and divergent national histories, the national varieties of Persian (Iranian, Afghan and Tajik) have coalesced around the pronunciation of their respective capital cities: Tehran, Kabul and Dushanbe. Most universities offering Persian as a second language – and this includes Chicago -- teach the modern standard Persian of Iran.

Because Iran has about twice the population of Afghanistan and Tajikistan combined, the Iranian word “Farsi” is sometimes also used in Afghanistan and Tajikistan as well, and since the 1960s and 1970s when large numbers of Iranians studied in the US and large numbers of Americans worked in Iran, the word “Farsi” has also been used in informal American English in place of Persian. In linguistic terms, however, Farsi refers to the particular national variety of Persian spoken in Iran, as distinct from the national varieties of Persian spoken in Afghanistan (Dari), or Tajikistan (Tajik Persian), in much the same way that American, Australian, British and Indo-Pakistani English are all distinct national varieties of the English language.

Persian is an Indo-European language, and therefore structurally related to English, with which it shares many cognate words (barâdar = brother, mâdar – mother, dokhtar = daughter, ast = is, am = am, etc.). In fact, Persian was one of the languages that led scholars like Sir William Jones to deduce the existence of a family relationship between English, German, Latin, Greek, Sanskrit and Persian as languages descended from a common sprachbund: proto-Indo-European.

Persian belongs to the Indo-Iranian branch of this family, which includes Sanskrit, Hindi, Punjabi, etc. But Persian’s more immediate relatives are found among the Iranian language family which includes the ancient scriptural language of the Zoroastrian religion, Avestan, as well as other now extinct languages such as Bactrian, Sogdian, Khwarezmian (Chorasmian), Saka, the Scytho-Sarmatian languages, and Parthian. The modern Iranian languages in use today, in addition to Persian, include Kurdish (Kurmanji and Sorani), Zaza, Ossetic, Luri, Pashto (the second official language of Afghanistan), and Baluchi.

Persian itself is roughly described as having three historical stages:

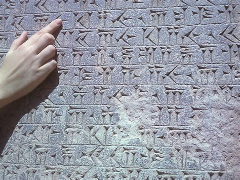

Old Persian was written in cuneiform, and used in the Achaemenid empire for royal inscriptions, seals and clay tablets, from the early 6th to the late 4th century BCE. Old Persian was an inflected language with multiple case endings, and singular, dual, and plural forms of the nouns.

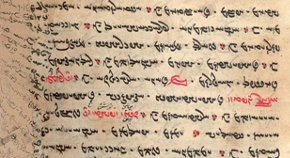

Middle Persian, including Parthian (Pahlawik) and Persian (Pārsīg and Pahlavi), was written using a modified form of the Aramaic script, both as a phonetic syllabary and as logograms. Middle Persian is attested in inscriptions of the Sasanian period and in book literature, mostly Zoroastrian confessional works, but also Manichaean and Nestorian texts, as well as secular literature, some of it orally transmitted for a while before being written down from about the 6th century CE well into the Islamic period in the 9th and 10th century CE.

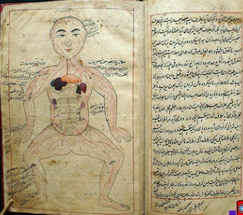

(New) Persian, written in the Arabic script, emerged in written form in the 10th century at the Saffarid and Samanid courts, and has remained fairly stable over the past millennium, so that texts like the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi (completed 1010 CE), can still be generally understood by Persian-speakers today. It is this new Persian that became the second language of learning (science, geography, history, administrative manuals), religion (exegesis, devotions, Sufi manuals, philosophy, theosophy), and literature (poetry, prose belles lettres, mirrors for princes) in the Islamic world, through which Islam was spread and promoted in Central Asia, South Asia and Seljuk Anatolia.

Apart from the many Persian words cognate with other Indo-European languages, some Persian words have been borrowed into Europe during the Middle Ages, or directly into English through the British in India, where Persian was an official language until the 19th century (such as lâzhvard – azure; tâfta – taffeta; pâdzahr – bezoar; shâh mât – checkmate; bakhshesh – bakhsheesh kamarband – cummerbund; kâravân = caravan; bâzâr – bazaar, khâki – khaki, etc.).

Persian in the Workplace

Because of the geopolitical significance of the area, Persian is a critical language for foreign and public policy, international development, international law, foreign service, national security, marketing and international trade. For anthropologists, archaeologists, historians, journalists, linguists, and other researchers, Persian has been an important language for fieldwork and research both in the Middle East and in diaspora communities in North America and elsewhere. In addition, the language is widely and extensively attested in painted, inscribed, or embossed material culture forms (murals, tiles, pottery, tableware, metalware, architectural and monumental inscriptions, jewelry, miniature painting). Persian is the language of the world-renowned cinema of Iran (including directors like Abbas Kiarostami, Asghar Farhadi, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Majid Majidi, etc.), and of many modern writers (e.g., Atiq Rahmani, Jalal Al-e Ahmad, Forugh Farrokhzad, Sadegh Hedayat, Shahrnush Parsipour, Zoya Pirzad).

Persian is historically the most important language and literature in the Islamic world after Arabic, with a vast and rich literary tradition, including poetry, prose belles lettres, historical chronicles, documents and correspondence, political treatises, philosophical treaties, religious (devotional, doctrinal, mystical, theological, heresiological, eschatological) tracts, scriptural texts (Islamic, Christian, Jewish, Zoroastrian, Baha’i), travelogues. Persian was the language of the primary chronicles, histories, and biographies of Iranian, Turkic, Central Asian and South Asian dynasties, as well as of treatises on kingship and statecraft, Sufism, philosophy, astronomy and belles lettres. Persian poetry was a critical inspiration for European Romanticism, with Sir “Oriental” Jones, Voltaire, Goethe, Ralph Waldo Emerson and many others translating, emulating or imitating Persian poetry. The Persian ghazal form shaped the Urdu and Turkish ghazal and has now given rise to the English ghazal.

Persian Study at UChicago

Students in the College can fulfill their language requirement with Persian, or use it as the basis for a Minor or Major in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations (NELC), or combine it with another program major (e.g., Fundamentals, Study of Gender and Sexuality, Global Studies, History, Human Rights, Political Science, Public Policy, etc.). MA students in CMES and in the Divinity School, MAPH or in MAPSS can focus on Persian language, literature, art, history and religions; and students in the PhD programs in Anthropology, Art History, Cinema and Media Studies, Comp Lit, Divinity, History, Music, NELC, Political Science, and SALC, etc., can pursue Persian as a major or minor research language. Graduate students often pair the study of Persian with other important languages of the region: Arabic, Armenian, Hebrew, Hindi, Kazakh, Syriac, Turkish, Urdu, Uzbek, etc.

Alongside the formal coursework, various extracurricular activities create and encourage opportunities on campus for students to practice colloquial speaking: our Persian Sofreh, a weekly Persian lunchtime conversation table; an occasional Persian Film Night, to watch and talk about classics of Iranian cinema; and a weekly Persian Circle (Anjoman-e sokhan) where various academic and cultural topics are presented in talks and formal lectures in Persian followed by Q&A.

Persian Student Essay Prize

Thanks to Lily Ayman Memorial Persian Studies Fund, the Department of Middle Eastern Studies will award one student in Intermediate Persian or other higher level Persian class with the Persian Student Essay Prize for the best written final paper. The prize will be presented at a Persian Studies reception at the end of spring quarter.

Prize recipients:

2023 Darragh Winkelman

2024 Indran Fernando

2025 Farah Akhtar

2025 Mert Aydemir

Persian Language, Culture, and Literature Courses Offered at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago offers two years of formal language-training in Persian, Elementary and Intermediate Persian, focusing on the four skills (listening, reading, speaking, writing). These courses meet four hours per week. Upon completion of the intermediate class, students have a firm basis in the language and can continue to expand their vocabulary, fluency and cultural command in various advanced survey courses, including Media Persian, Persian Literary Translation, the Persian Short Story, the Persian Ghazal, Persian Prose, Persian Sufi Texts, Modern Scholarly Prose, as well as courses about specific authors and themes (the Shâhnâmeh, Jalâl al-Din Rumi, Women Writing Persian, Nezâmi, Farid al-Din Attâr, Sanâ’i, Sa`di, Bidel, and other courses in Persian literature).

Persian Language Courses Offered in 2025-2026

PERS 10101-02-03 Elementary Persian (Autumn-Winter-Spring) (Dr. Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi) This sequence concentrates on all skills of language acquisition (reading, writing, listening, and speaking). The class begins with the Persian alphabet, and moves to words, phrases, short sentences, and finally short paragraphs. The goal is to enable the students towards the end of the sequence to read, understand, and translate simple texts in modern standard Persian and engage in short everyday conversations. All the basic grammatical structures are covered in this sequence. Introducing the Iranian culture through the texts is also a goal. The class meets four hours a week with the instructor and one hour with a native informant who conducts grammatical drills and Persian conversation.

PERS 20101-02-03 Intermediate Persian (Autumn-Winter-Spring) (Dr. Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi) This sequence deepens and expands the students' knowledge of modern Persian. The goal is to enable the students to gain proficiency in all skills of language acquisition at a higher level. In this sequence, the students learn more complex grammatical structures and gain wider vocabulary through reading paragraph-length texts on a variety of topics related to Persian language, literature, and culture. Students will also be familiarized with Persian news and media terminology. Class meets four hours a week with the instructor and one hour with a native informant who conducts grammatical drills and Persian conversation.

Wit and Wisdom in Persian Quatrains: Omar Khayyam, Mahsati, 'Attar, and Others (Autumn 2025) (Dr. Austin O’Malley)In this course, students will learn to read, understand, and recite Persian quatrains (roba'iyat): short, two-line poems that often end with a witty "punchline," funny or profound. We will explore quatrains attributed to several figures including Omar Khayyam, the 12th-century philosopher; 'Attar, the 13th-century Sufi poet; and Mahsati, one of the best-known female poets in the canon and a member of Sultan Sanjar's mid-12th-century court. Special attention will be paid to the various oral and textual means of these poems' transmission, including anthologies and compilations. To contextualize these verses, we will analyze selections from Persian rhetorical writings, histories, and hagiographies that shed light on the quatrain's meter, origin, and function within various courtly, intellectual, and religious settings. In addition to Persian-language primary sources, the course includes secondary source readings in Persian and English, but the language of class discussion will be English. One year of prior Persian-language study (or equivalent) is required and two years are recommended.

Persian Language Courses not offered in 2025-2026

PERS 30331 Love and War: The Romance and Epic Traditions in Premodern Persian (not offered in 2025-2026) (Dr. Austin O’Malley) This advanced reading course introduces students to the intertwined epic and romance genres in premodern Persian. Through engagement with the original sources, students will become familiar with the vocabulary, grammatical features, poetic topoi, and metrical rules necessary to read, understand, and analyze key selections from Ferdowsi, Neẓāmi, Amir Khosrow, Jāmi, and other poets. In addition to developing their linguistic skills and familiarizing themselves with central texts of the premodern Persian canon, students will also engage with both Persian- and English-language scholarship on the tradition. This course is open to those who have completed two years of Persian or the equivalent.

PERS 20500 Media Persian (not offered in 2025-2026) (Dr. Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi) This course provides students with an opportunity to read authentic texts in Persian. Through various exercises, the students will be familiar with the news terminology as well as other complex expressions and proverbs used throughout the news articles that encompass different themes related to Iran’s politics, literature, culture, economy, etc. During this course, you will read a variety of news excerpts from the newspapers printed inside Iran (Ettelā’āt, Keyhān, Sharq, E’temād, Irān, and Mardomsālāri) and follow their current status as reflected in today’s media. Class meets three hours a week with the instructor and one hour with a native informant who conducts grammatical drills and Persian conversation.

PERS 20502 Persian Literary Translation (not offered in 2025-2026) (Dr. Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi) This course aims at strengthening the proficiency level of students beyond the intermediate level. Through a survey of translation techniques and strategies, students will do hands-on translations of various kinds of literary texts, both prose and poetry, both classical and modern. In addition, students will be introduced to prevailing theories of translation and the most efficient methodology of translating Persian literary texts by means of a close comparison of translated texts with the original. As term project, students will translate a short story or a long poem, either classical or modern from Persian into English. Class meets two days per week, each session for an hour and a half.

PERS 20502-NEHC 22502/32502 Persian Literary Translation: Through the Translation of Hafez (not offered in 2025-2026) (Dr. Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi) Translating poetry is often a challenging endeavor, but translating Persian classical poetry is especially complex for several reasons, including the genre’s prevalence of ebhām (ambiguity) and ihām (polyvalence). These challenges have caused many literary translators to dub Hafez’s poetry as practically untranslatable, yet nonetheless there have been many attempts at translation, with varying degrees of success. This course aims to both explore the specific challenges translators of Hafez have encountered and also to strengthen students’ literary translation skill through the translation of Hafez’s ghazals. Through reading about translations of Hafez and other Persian classical poets and hands-on translations of several ghazals of Hafez, students will foster a better understanding of the multilayered meanings of his poetry. In addition, published as well as video sources on literary translation will serve as an introduction to prevailing theories of translation and to efficient methodologies of translating literary texts.

PERS 20021/30021 Persian Short Story and Translation (not offered in 2025-2026) (Dr. Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi) Persian short story writing began in the twentieth century with Mohammad-Ali Jamalzadeh’s collection Yek-ī būd yek-ī nabūd (1921). The 1920s through the 1940s is considered the formative period of Persian short-story writing, also known as the first period. The second period in the development of the modern Persian short story began with the coup of 28 Mordād 1332/19 August 1953 and ended with the 1979 revolution. The third period that started after the 1979 revolution has been called the period of diversity in that it brought forth a variety of literary movements. In this course, we will review the three periods of Persian short story development mentioned above to give you historical background on this genre of Persian literature. However, the focus of readings in this course is the short stories written by Hedayat, Daneshvar, Pirzad, Golshiri, Esma’ili, and others who have employed elements of fantasy, surrealism, and the paranormal in their stories. The class meets twice per week, each time for an hour and a half. We will read the original stories in Persian, translate some sections and discuss them in class in Persian.

Iranian/Persian Studies Core Courses offered in 2025-2026

NEHC 20601/HIST 25610/SOSC 22000/RLST 20401/MDVL 20601 Islamic Thought and Lit I (Autumn 2025) (Dr. Austin O’Malley) In the first quarter of Islamic Thought and Literature, students will explore the intellectual and cultural history of the Islamic world in its various political and social contexts. Chronologically, the course begins with emergence of Islam in the 7th century CE and continues through the Mongol conquests until the rise of the "gunpowder empires" circa 1500. Students will leave the course with a historical and geographical framework for understanding the history of the Middle East and a familiarity with the major forms of premodern Islamic cultural production (e.g., history-writing, scriptural exegesis, poetry, philosophy, jurisprudence, etc.). Students will also develop the skills and contextual knowledge necessary for analyzing these sources in English translation; they will thus come to appreciate premodern Islamic cultural products on their own terms while engaging in the collective work of historical interpretation. No prior background in the subject is required. This sequence meets the general education requirement in civilization studies.

Love, Sex, and Desire in Middle Eastern Literature (Spring 2026) (Dr. Austin O’Malley) Course Description TBD

NEHC 20151 / NEHC 30151 Modern Iran: Through Film & Literature in Translation (Spring 2026) (Dr. Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi) In this course we will examine modern Iran through film and literature. We will investigate the distinct characteristics of pre- and post-revolutionary Iranian society through Persian films, novels, short stories, and poetry in English translation. Discussions for the pre-revolutionary period will revolve around social justice; political and religious corruption; poverty and political dissent, and other contribution factors to the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran. Post-revolutionary topics include themes such as class, representations of Islam and the clerical establishment; social problems; gender politics; women's social, economic, and political roles; the struggle between modernity and traditionalism in contemporary Iran; and the symbolic language of modern Iranian cinema as well as censorship and its role in creating the Iranian contemporary literature.There is no prerequisite for the course and no knowledge of Persian is required. All readings are in English translation and the films are with English subtitles. The course includes lectures deconstructing political, religious, and social evolution of modern Iran as well as regular class discussions where we will address the issues in question from a variety of perspectives using a diverse range of sources to give us a bird’s eye view of the issues at stake.

RLST 28101- ISLM 38101- AASR 38101 Iblis: Muslim Perspectives on the Devil (Spring 2026) (Dr. Alireza Doostdar) This course examines a range of Muslim perspectives on the Devil. Is Iblis a personification of evil, an archetype of arrogant rebellion against divine command, a perfect monotheist and tragic lover of God, or an ally of humankind and teacher of freedom and creativity? Our readings will include selections from the Qur'an and hadith, Sufi poetry, modern political and theological writing, and others.

RLST 24550 SIGN 26068 MDVL 24550 GLST 24550 ISLM 32419 Major Trends in Islamic Mysticism (Spring 2026) (Dr. Yousef Casewit)An examination of Islamic mysticism, commonly known as Sufism, through English translations of premodern and contemporary Sufi literature originally composed in Arabic and Persian. The aim of this course is to gain firsthand exposure to a wide range of literary expressions of Islamic spirituality within their historical contexts, and to understand exactly what, how, and why Sufis say what they say. Each unit consists of lectures and close readings of selected excerpts in both the original Arabic/Persian and English translation. Weekly reading assignments average 50 pages.

ISLM 36103/RLST 26103 Dreams, Visions, and Mystical Experience (Spring 2026) (Dr. Yousef Casewit) The primary goal of this course is to explore primary and secondary literature on dreams, visions, and mystical/religious experience. As we move through the three sections of the course, we will pay close attention to three overarching themes: 1) Phenomenology: What are the distinctive characteristics and subjective features of the experience? What does the experience mean to the person involved? What is it like to have the experience and to try to express it? How can we classify and schematize the experience in relation to others? 2) Epistemology: What does the experience mean within the experiencer’s religious tradition? What meaning-making frameworks exist within the experiencer’s tradition to make sense of, interpret, and integrate the event? 3) Hermeneutics: What could the experience mean someone who subscribes to a different explanatory model, or to someone from a different tradition? What can the experience of an Ibn ʿArabi mean to a modern historian, or to a Shaman? Consider the experience from the perspective of a different religious framework or a secular model (William James, Rudolph Otto, Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Henri Corbin, psychology of religion, secular models of the psyche, contemporary philosophers of religion).

Iranian/Persian Studies Core Courses not offered in 2025-2026

NEHC 22708 Persian Literature in “the West”: Transcendentalism to New Age Spirituality (not offered in 2025-2026) (Dr. Austin O’Malley) Although we may have passed “peak Rumi,” Persian poetry is still often translated and consumed as a component of modern “global” spirituality, and poets like Hāfeẓ and Rumi are frequently understood to be universalizing mystics. This course explores how Persian poetry has been adapted into European languages and interpreted over the past two hundred years, from Transcendentalists to New Agers, with a particular focus on how it has been variously invested with religious or “spiritual” meaning in Euro-American contexts. Class readings include a variety of translations of Persian poetry; secondary sources on translation, reception, and “world literature”; and theoretical critiques of “religion” and “mysticism” as analytic categories. All readings are in English, and no prior familiarity with Persian or the Persian language is required.

NEHC 20014 Ancient Empires IV: The Achaemenid Empire (not offered in 2025-2026) (Dr. Mehrnoush Soroush) This course introduces students to the Achaemenid Empire, also known as the First Persian Empire (ca. 550-330 BCE). We will be examining the political history and cultural accomplishments of the Achaemenids who, from their homeland in modern-day Iran, quickly rose to become one of the largest empires of the ancient world, ruling from North Africa to North India at their height. We will also be examining the history of Greek-Persian encounters and the image of the Achaemenids in Greek and Biblical literature. The students will visit the Oriental Institutes’ archive and object collection to learn more about the University of Chicago’s unique position in the exploration, excavation, and restoration of the Persian Empire’s royal architecture and administrative system through the Persian Expedition carried out in the 1930s.

Major and Minor

Students who pursue a Program of Study (Major or Minor) in NELC can choose to focus on the Persian language and culture, within the frame of the NELC Major and Minor requirements. Here is a summary of these requirements, alongside examples of how they can be adapted to the study of Persian specifically:

NELC Major with a focus on Persian, Language and Culture Track Requirements:

Students are encouraged to track their progress through requirements by using our Language and Culture Track Major Worksheet.

- Civilization Sequence: Two or three quarters of a sequence listed below. If a NELC civ sequence is used to meet the College general education requirement, a second Near Eastern civilization sequence is required for the NELC major:

- NEHC 20011-20012-20013-20014-20015-20016-20017. Ancient Empires I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII

- NEHC 20004-20005-20006. Ancient Near Eastern Thought and Literature I, II, III

- NEHC 20201-20202-20203. Islamicate Civilization I-II-III (see note below)

- NEHC 20601-20602-20603. Islamic Thought and Literature I, II, III

- JWSC 12000-12001.Jewish Civilization I-II.

- Languages: Six courses in Persian. With approval of DUS, students may combine courses in related languages. Credit for language courses may not be granted by examination or placement.

- Electives: Three or four elective courses in the student’s area of specialization, in this case the languages, history, and culture of the Persian world. Students should discuss their planned coursework with the instructors in the Persian program and the DUS. NEHC 29995 Research Project may be counted towards the elective requirement.

- The Research Colloquium (NEHC 29899) is required of all NELC majors. It is to be taken in the Autumn Quarter of the year in which the student expects to graduate. See the Research Project section for more detailed information.

PLEASE NOTE: The course sequence on “Islamicate Civilization” does not fulfill the general education requirement in civilization studies. All of the other NELC civilization sequences do fulfill the general education requirement.

NELC Minor with a focus on Persian, Language Track requirements:

The Language Track includes at least three courses in Persian. If a NELC sequence is used for the general education requirement in civilization studies, a Language Track minor can also consist of six language courses in Persian or in Persian and another related language with DUS approval. Here are some examples of possible combinations — please consult with the Persian Language Coordinator and the DUS to evaluate your individual needs.

Language Track in Persian Sample Minor

| NEHC 20201-20202-20203 Islamicate Civilization I-II-III | |

| PERS 10101-10102-10103 Elementary Persian I-II-III* |

OR

| NEHC 20601-20602-20603 Islamic Thought and Literature I-II-III |

| PERS 20101-20102-20103 Intermediate Persian I-II-III* | |

OR NEHC 20601-20602 Islamic Thought and Literature I-II PERS 20101-20102-20103 Intermediate Persian I-II-III* PERS 20502 Persian Literary Translation * |

Language Track in Persian Sample Minor (for students who take a NELC sequence to satisfy civilization studies requirement)

PERS 10101-10102-10103 Elementary Persian I-II-III* PERS 20101-20102-20103 Intermediate Persian I-II-III* | |

OR (with placement into the Elementary Persian sequence) PERS 10103 Elementary Persian III* PERS 20101-20102-20103 Intermediate Persian I-II-III* PERS 20500 Media Persian* | |

PERS 20502 Persian Literary Translation * OR (with two-language option) PERS 10101-10102-10103 Elementary Persian I-II-III* ARAB 10101-10102-10103 Elementary Arabic I-II-III* |

*Consult the Director of Undergraduate Studies about the level of the language (introductory, intermediate, or advanced) required to meet the language track requirement. Credit may not be granted by examination to meet the language requirement forcthe minor program.

Persian Placement Test

A placement test for incoming first-year undergraduates can be arranged through CLC.

For further questions contact: Dr. Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi (pshabanijadidi@uchicago.edu). Incoming graduate students uncertain about their level can also arrange to take a placement exam.

Persian Circles 2025-2026

AI-Driven Language Pedagogy for Less Commonly Taught Languages Webinar Winter 2026